The Treasury has become a revolving debt line of epic proportions to avoid default. But what will happen when the gloves are off?

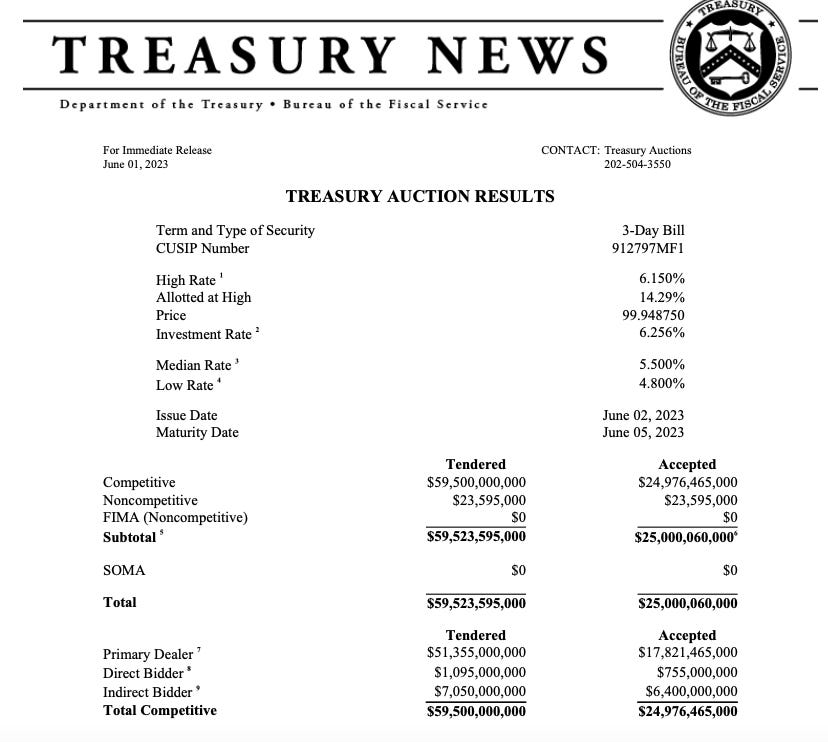

This week, I was shocked to learn that for the first time (at least for as long as I can remember) the Treasury issued a 3 DAY Bill, marketable on June 2nd and maturing Monday, June 5th.

However this surprise was short lived, when only minutes later I saw that they had also issued a 1 day bill, an instrument that is virtually indistinguishable from the securities in the Fed’s Reverse Repo window. Yellen is essentially morphing the government into a giant revolving credit machine, with the introduction and use of shorter and shorter maturity debt to finance government operations.

The Treasury is turning into a credit card of epic proportions.

Image courtesy of James Lavish

To best understand why the Treasury went ahead with these incredibly short maturities, it’s best to understand the origins of the short-duration Treasury bill itself.

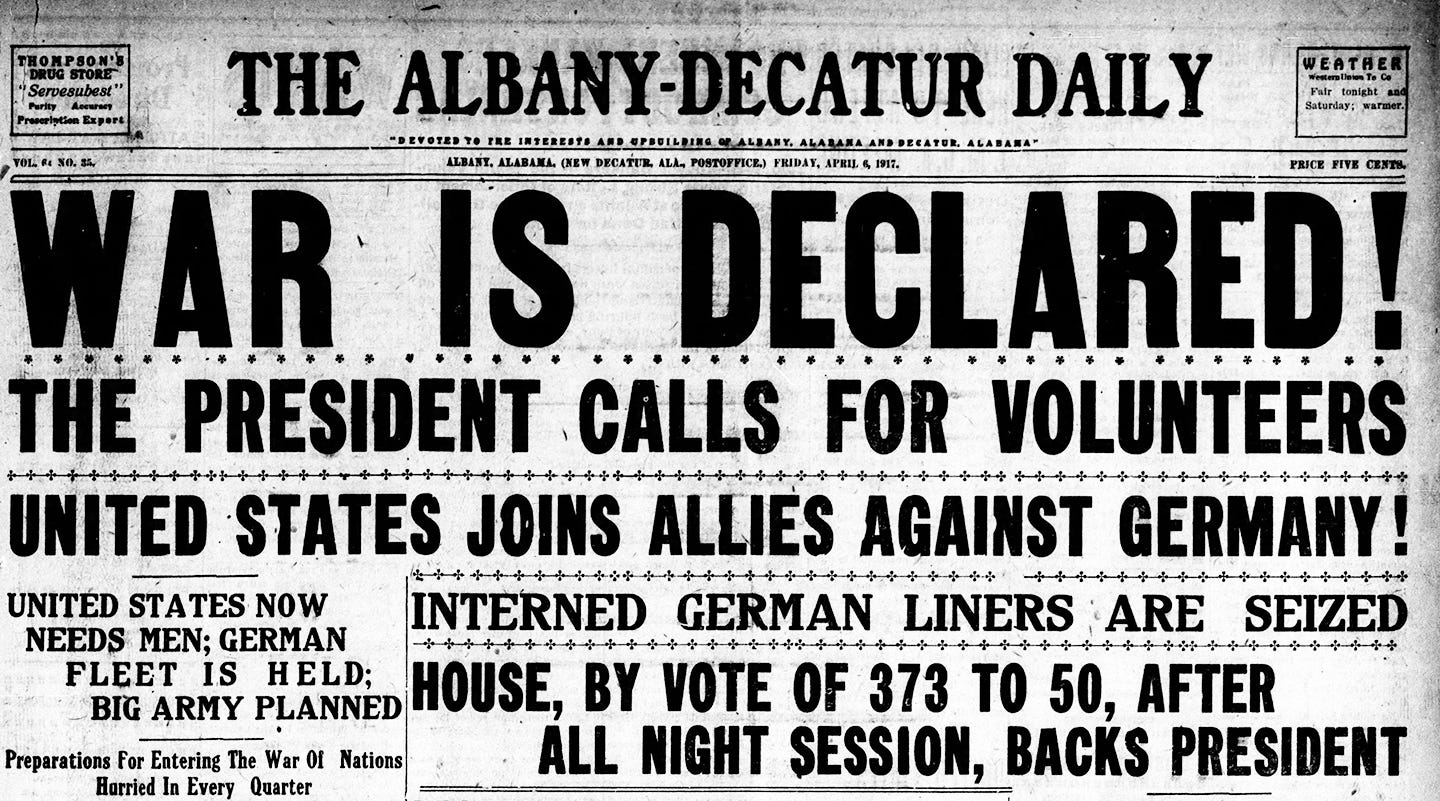

The United States joined World War I on April 6, 1917, which sparked a long-lasting national debate on whether the war should be funded through debt or taxes. Senator Furnifold Simmons of North Carolina, who leaned towards the side of debt financing, argued that the country had traditionally paid war expenses through bond issues and saw no reason to change that approach. J. P. Morgan, the nation's prominent financier, agreed and believed that only 20 percent of war costs should come from taxes.

However, combating the debt issuance side was William McAdoo, President Wilson's Treasury Secretary during the war. He, along with Wilson, preferred that half of the expenses be covered through taxes. Moving further along the political spectrum, the New York Times reported that some members of Congress proposed funding 75 percent of the first-year expenses through taxation.

The debate between tax and debt financing of the war was soon resolved. With the rapidly increasing cost of operating the growing war machine in Europe and the public’s vehement anti-tax beliefs, debt financing was the only way that Congress could fill the deficits quickly enough.

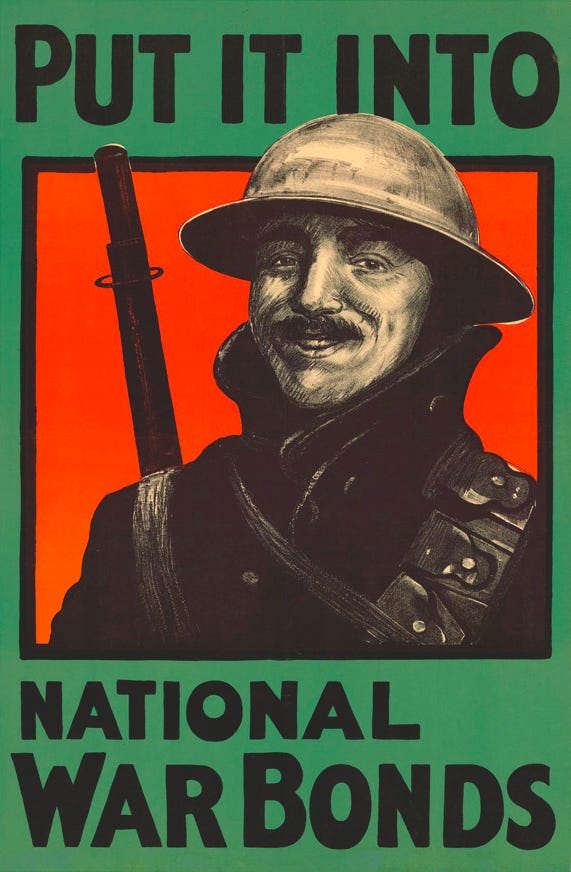

The Treasury raised a gargantuan $21.5B by issuing large Liberty bonds during the war along with shorter term “certificates of indebtedness” that netted an additional $3.45 billion. These securities had coupon rates set by Treasury officials and were sold at par over a subscription period that would last several weeks.

To facilitate these sales, the Treasury and the twelve Federal Reserve banks managed a system of War Loan Deposit accounts at commercial banks across the country. A bank typically paid for its own and its customers’ purchases of Treasury securities by crediting the War Loan Deposit Account that the Treasury maintained at the bank. When funds were needed to meet expenses, the Treasury would request that some of the balances be transferred to Treasury accounts at Federal Reserve Banks (from which the Treasury paid most of the bills of the federal government).

However, this system had several flaws. First, the interest rates paid on War Loan Deposit accounts was around 2%, while the average Treasury bond paid out around 5%. This resulted in negative carry on the account balances, as the Treasury was paying interest far above what it was receiving on its own deposit accounts. Furthermore, these War Loan deposit accounts were not immediately drawn, so the banks could credit the account without funding it, buy Treasuries, and sell them on the secondary markets, often for more than they bought them for. When the Treasury started to draw on the account, they could then move money into it to satisfy their obligations. This was essentially front-running the Treasury and was a common practice.

Second, Treasury financing operations usually were conducted on quarterly tax dates, so that money coming in from tax revenue could be immediately used to pay off maturing notes. However, there was often a problem- the tax receipts would come in late, or not be enough to fund the payments for maturing notes. Thus, the Treasury had to go out into the money markets and borrow money overnight from banks, draining reserves from the system and causing short term interest rate volatility.

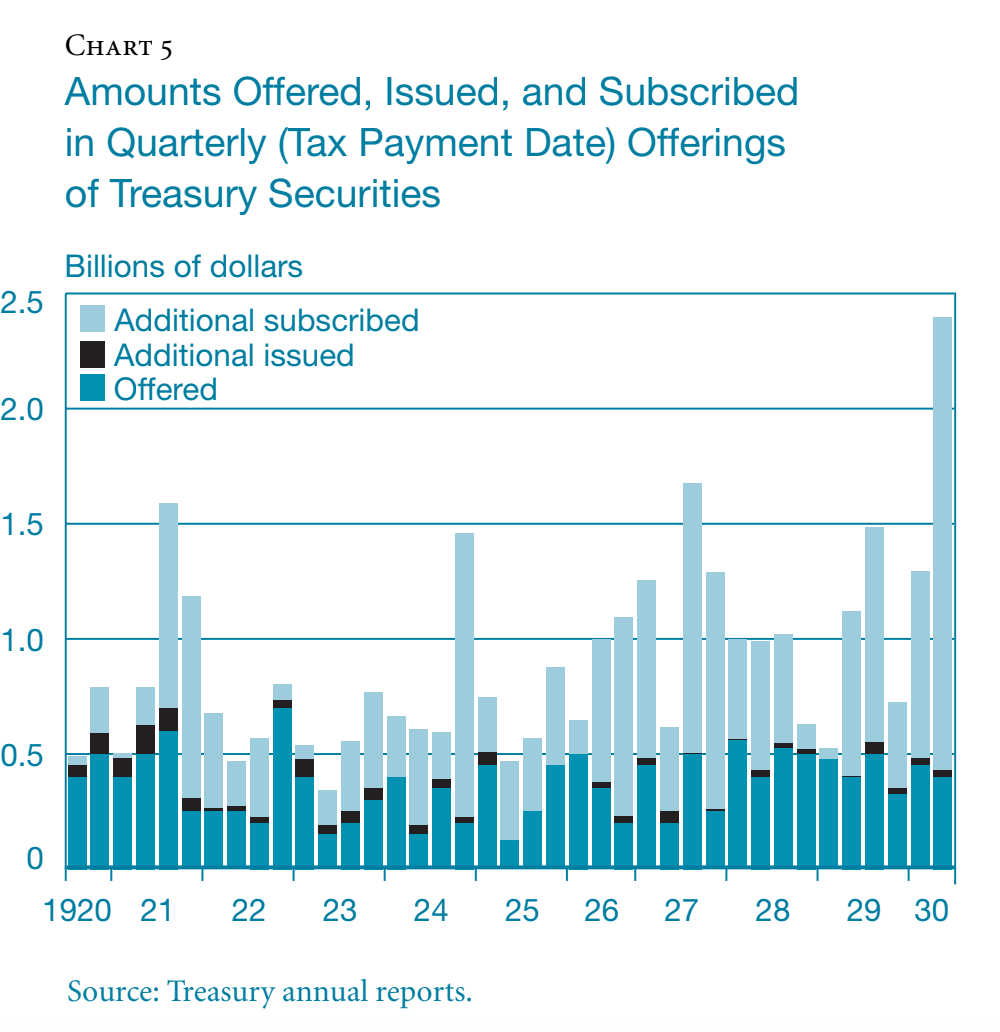

Third, and maybe most important, was that the short term debt at the time, “certificates of indebtedness”, were offered infrequently and at fixed-price sales, almost always below market price. This was ostensibly to avoid a failed Treasury raising, as some offerings in 1920 and 1922 had resulted with insufficient cash raised and a “re-valuing” of the bonds to a lower level in order to increase subscriptions and raise enough money.

In 1929, four new ideas were proposed by J. Herbert Case, Deputy Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, who had just traveled to London to see the British Treasury market in action:

1) Treasury bills would be auctioned rather than offered for sale at a fixed price. He pointed out that “Competitive bidding . . . might be expected to enable the Treasury to get the lowest discount rates consistent with current market conditions; it would not be necessary for the Treasury . . . to offer interest rates on new issues above current market rates.”

2) Bills would be sold when funds were needed.

3) Bill maturities would be set “to correspond closely to the actual collection of income taxes, and not all made to fall on the nominal date of tax payments as at present.”

4) Sales would be for cash, instead of credits to War Loan Deposit Accounts.

Congress quickly approved the proposed legislation, and President Hoover signed it into law on June 17, 1929. During the following six months, Treasury officials worked out the details of the new security, such as the wording that would appear on the face of a bill and how it would be sold to the public. In December, the first Treasury bill was proffered with a term of 90 days. The auction went off without a hitch.

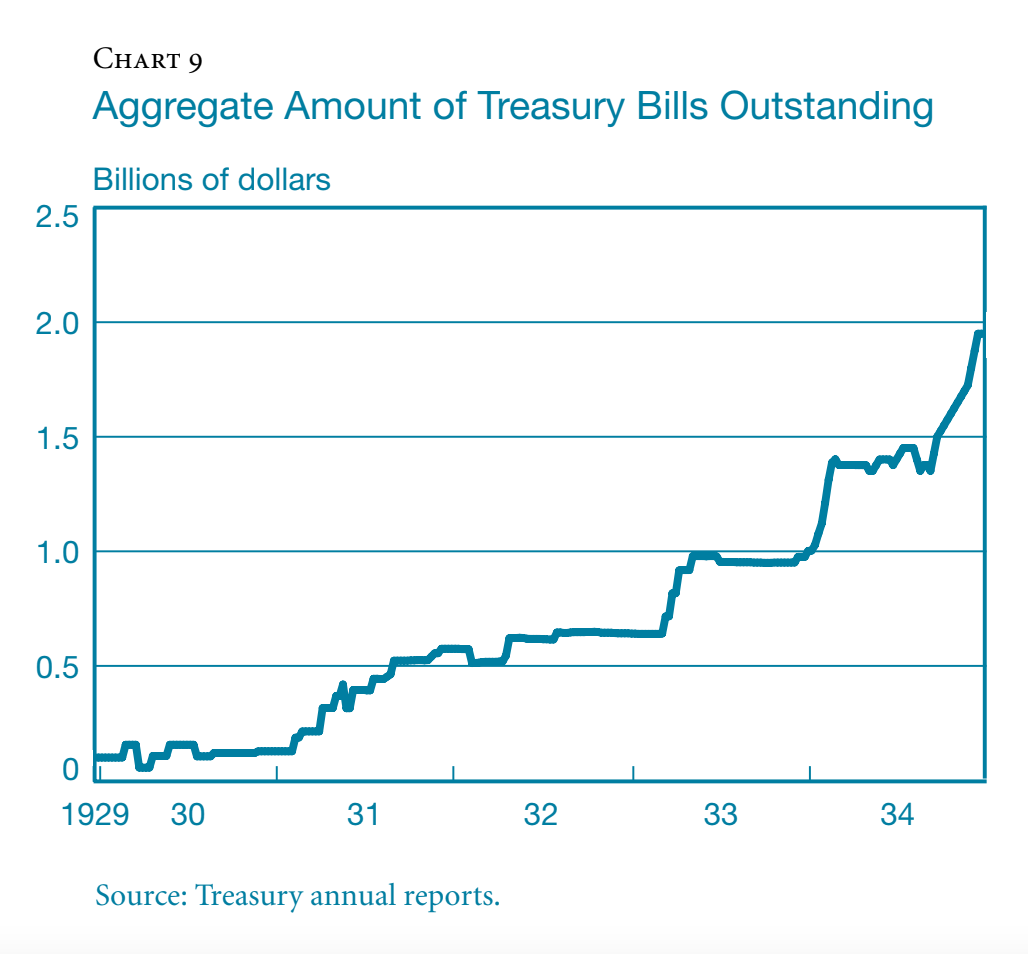

Treasury bills would gain increased adoption over the next few years, eventually becoming a key part of financing the government, with bills offered whenever short term cash was needed. Today, Treasury bills with durations of 4, 8, and 12 week durations are commonplace at auctions.

The new three day bill was issued this last Friday to help the Treasury hold out over the weekend. Currently, only about $37B sits in the TGA, the Treasury General Account- which is essentially the government’s checking account. They desperately need this money to finance government operations until Monday when new debt issuances can be sold.

The investment rate ended extremely high- 6.256%, well above where most short term Treasuries are trading at now. Not surprisingly, a huge amount was tendered for this issuance- over $59 billion!

However, this is not even the shortest maturity being issued- like many Twitter users and Jeff Snider himself pointed out, the Treasury is set to auction $15B worth of 1 day bills with an equivalent coupon-issue yield of 5.145% on Monday that will be repaid by Tuesday morning.

All this comes about as the week of June 5th marks a period of significant outlays- Yellen herself warned Congress in a letter last week that Treasury has $92B of obligations to fulfill that week, and there isn’t enough cash to meet all the demands.

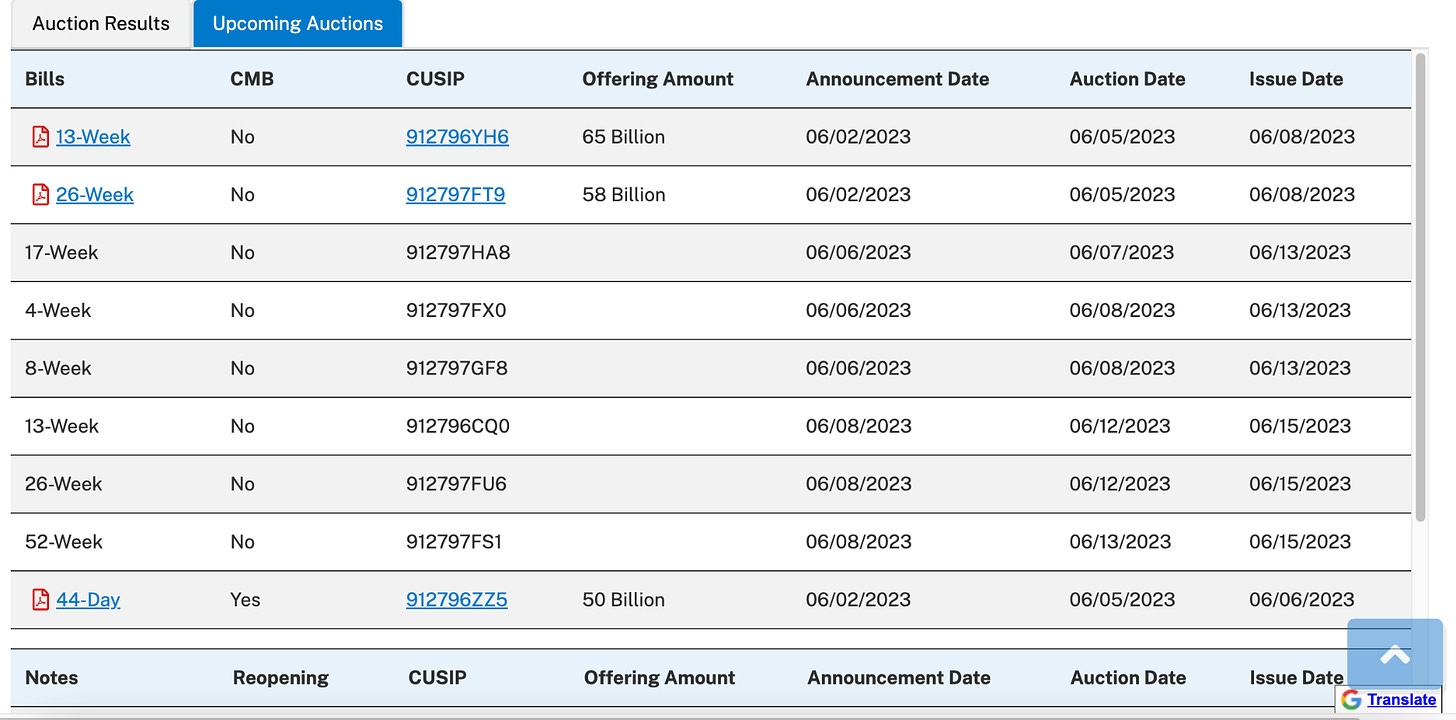

To remedy this, the Treasury is not only offering these incredibly short duration bills, but also dumping $173B in 13-week, 26-week, and 44-day notes all on the market on Monday, June 5th to raise enough cash to satisfy spending needs.

Now, with the debt ceiling deal passed by the House and Senate and signed by Biden this weekend, it has officially become law- and unfettered Treasury borrowing is once more a reality.

Over the course of June, Yellen will likely have to raise around $1T in new funds to refill the TGA, draining liquidity from the banking system. The Treasury General Account is a liability held at the Fed, and any changes in the TGA affect reserve balances. As the TGA increases, it leads to a decrease in reserves, which can result in reduced liquidity levels in the markets.

This is not to say that a stock market rout is guaranteed- but all things being equal, less liquidity in the banking system is certainly not good for the banks.

To say that the continued use of these extremely short term debt instruments will become commonplace remains to be seen. All of these acrobatics are done to avoid missing a payment on any government obligation- the Treasury must remain nominally money-good, no matter what.

A Billion Dollar Credit Card.

Originally written on Dollar End Game