And will it happen?

What happens if Argentina gets rid of its Central Bank? Will Argentinians be carrying around a pocketful of greenbacks or — better yet — gold coins while unemployed bankers shine shoes?

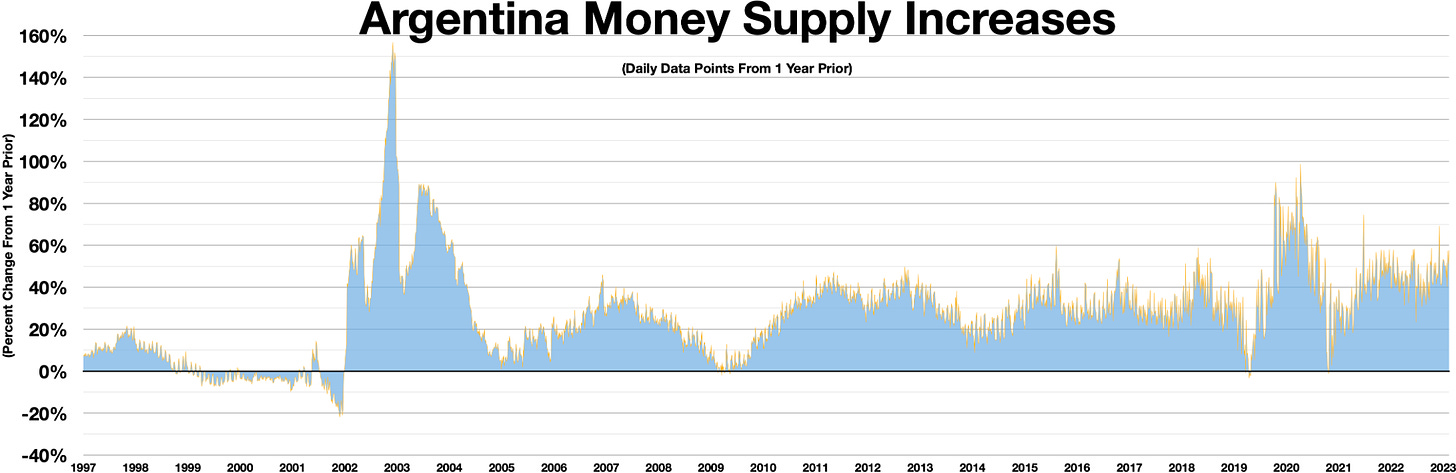

Last week I wrote about how governments cause hyperinflation, using Weimar Germany and the current hyperinflation ravaging Argentina. This week I want to focus on one of the solutions -- and the one Javier Milei is proposing -- dollarization.

On December 10 Javier Milei takes office after his "shock" win in the Argentina election. He's promising to close the central bank and ditch the currency.

What would it look like?

In short, going by other dollarizations it would reduce inflation dramatically, leading to much faster economic growth and prosperity. And it would make Argentina's banks stronger, reducing the risk of a financial crash. Put it together and Argentina would go from perennial basketcase to well on its way to prosperity.

Finally, will it happen. The punchline there is it’s not nearly as hard as it looks. Meaning Argentina could inspire many other countries to follow suit.

Ever since Walter Bagehot's seminal 1873 book "Lombard Street," the two main functions of a central bank are money printing and banking regulation -- regulation meaning, in practice, bailing out insolvent banks.

Money printing means the central bank decides how much new money should be created -- counterfeited, if you prefer. This is mainly done using interest rates: Lower rates mean more money is created, generally by banks lending it into existence. Higher rates reduce money creation.

The second function is banking regulation. That includes some boring things like oversight of payment rails, which would probably be transferred to the Ministry of Finance if the central bank didn't exist.

But the economically important part of central banking regulation is deciding how much money commercial banks can create. This is also influenced by interest rates, but mainly by the central bank's

willingness to bail out insolvent commercial banks.

This is called the "lender of last resort" function, and it's a bedrock of central banking ever since Bagehot. If a bank is insolvent and nobody else will lend it money, the central bank will still lend. In other words, it's a standing offer to bail out.

And banks, knowing this, can run wild with risk: They're gamblers who get to keep their wins but their losses are covered.

If you close the central bank, beyond trivial transfer of payments oversight, the main impact is you're effectively ditching the local currency. In Argentina's case replacing it with the US dollar.

This would take Argentina out of both of those main central bank functions: money printing and bailouts.

That means no more direct money printing -- the central bank can't buy government deficits to create new money. And it would take Argentina out of the interest rate game — rates would be set by the Federal Reserve instead.

Meaning no more home-grown negative interest rates to spawn "tissue fire" booms and busts.

Both would reduce Argentina's inflation dramatically, but not completely. For two reasons.

First, adopting the dollar essentially means adopting the US inflation rate. Which is a lot better than Argentina, but it's still running around 4% with potentially more to come.

Second, even without a local central bank, Argentinian banks could still print money via fractional reserve banking. Fractional reserve meaning they lend money they don't have knowing they'll get bailed out.

The bail-outs wouldn't be as generous, of course, since any bail-out would have to come from Argentina's Ministry of Finance or they'd have to beg the US to do it like Mexico did in the 1990's.

Both are tougher bail-out asks than a central bank, who can just print money at the touch of the button. After all, the Ministry has to use hard-to-get dollars, while American voters might not be enthusiastic about bailing out of Argentinian banks.

Summing it up, for Argentina, getting rid of the central bank dramatically reduces inflation. Because it completely eliminates direct money printing -- about half of the total, going by M1. And it dramatically reduces fractional reserve printing -- the other half.

So what are the odds?

The key hurdle for Milei is that he lacks a Congressional majority. Meaning he has to rely on public pressure on Congress.

Having said, dollarization -- replacing the local currency with the dollar -- isn't as radical as it looks. Both Ecuador and El Salvador dollarized recently, ditching their basketcase currencies for the US dollar under conventional governments. Both kept their central banks, but without a currency it's basically a janitor.

Both countries swapped out their national currencies for the US dollar around 2000, and both benefitted massively, going from among the poorest countries in Latin America to a lot closer to normal.

Taking the before and after, before dollarization El Salvador's annual inflation rate was about 15%, and Ecuador's was about 40%. After dollarization, both averaged 1.5% per year -- about one fifth the rate of the rest of Latin America. For comparison, over the same period Argentina ran inflation of 39% per year.

As a consequence, when they dollarized, El Salvador had about half the average income as the rest of Latin America, and Ecuador was at one third. In the following 20 years, El Salvador grew about 30% faster than the rest of Latin America, while Ecuador grew two and a half times faster -- almost 7% per year, which is “tiger” levels. Argentina, meanwhile, grew at just 0.5% per year.

Today, 20 years later, El Salvador and Ecuador both have unemployment rates at or under 4%. Argentina's is 11.5% even according to official numbers.

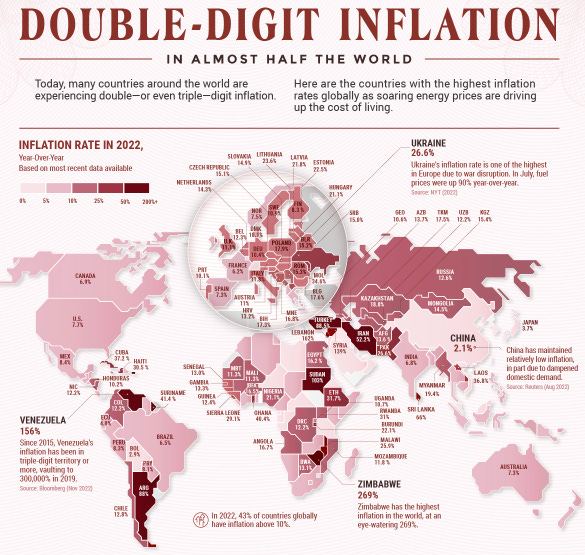

Given this record, it shouldn't take a libertarian radical to dollarize. In fact, every country currently suffering high inflation should be dollarizing right now, of which there are currently dozens from Venezuela to Lebanon to Turkey to Ethiopia.

As for Argentina, whether or not Milei manages to formally shutter the central bank, if he manages to dollarize it will be a godsend for the long-suffering people of Argentina.

He's catching criticism for swapping the peso for the dollar instead of going all the way to gold or even Bitcoin. But voters will only go so far in a single bound, and the dollar's still a damn sight better than the local confetti.

Whether he succeeds will ultimately depend on his ability to keep the people on-side to push reform through a presumably hostile Congress. But simply putting the topic of currency reform on the policy table will have done an enormous service to Latin America as well as the dozens of countries currently mismanaging their currencies to oblivion.

Sign up to my free email list to get weekly posts on the economy and freedom. Choose the $5 option if you’d like to support the videos and articles and keep everything paywall free!

Also check out the weekly podcast rounding up all the week’s videos in a single 30 minute podcast.

Originally published on profstonge.com