The U.S. government's $11 trillion spending spree is reshaping the economy, raising questions about its long-term health and stability.

The U.S. economy has been under the spotlight due to the substantial fiscal spending of the federal government, which have led to unprecedented levels of borrowing and financial redistribution. With demand destruction becoming more evident, it becomes crucial to explore the consequences of these activities on the economy, especially as we progress into 2024.

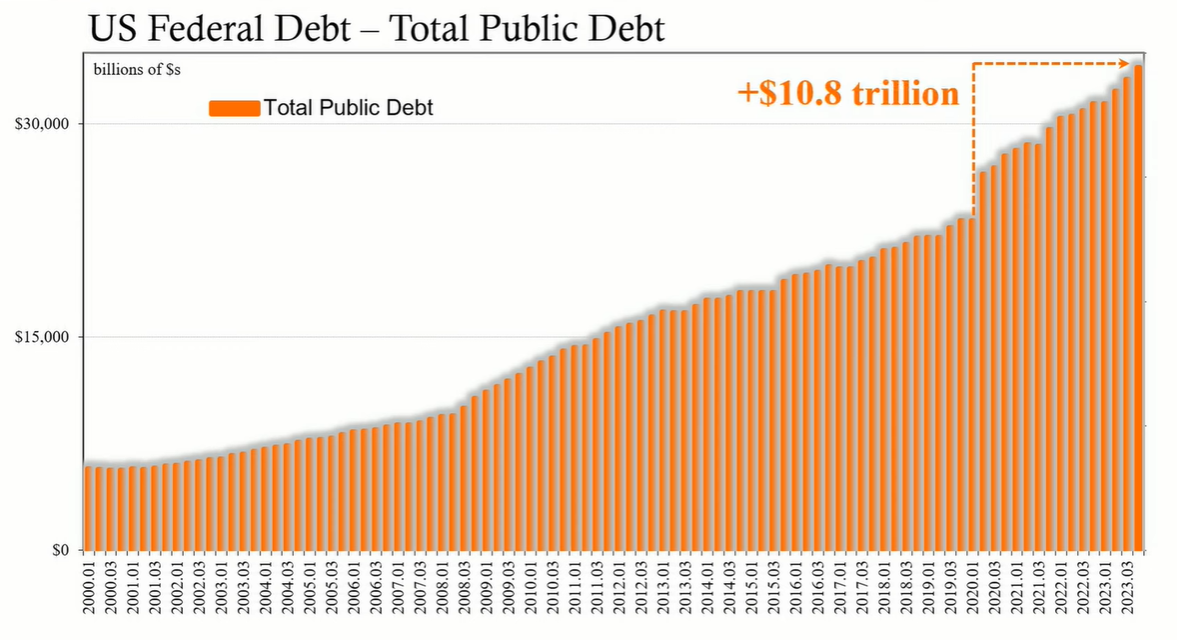

The US federal government has significantly increased its borrowing since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The total public federal debt has risen by approximately $10.8 trillion since the first quarter of 2020, with $2.5 trillion of that amount accumulated in the last three quarters of the previous year. Such borrowing has been directed towards various transfer payments, including government social benefits and business aids.

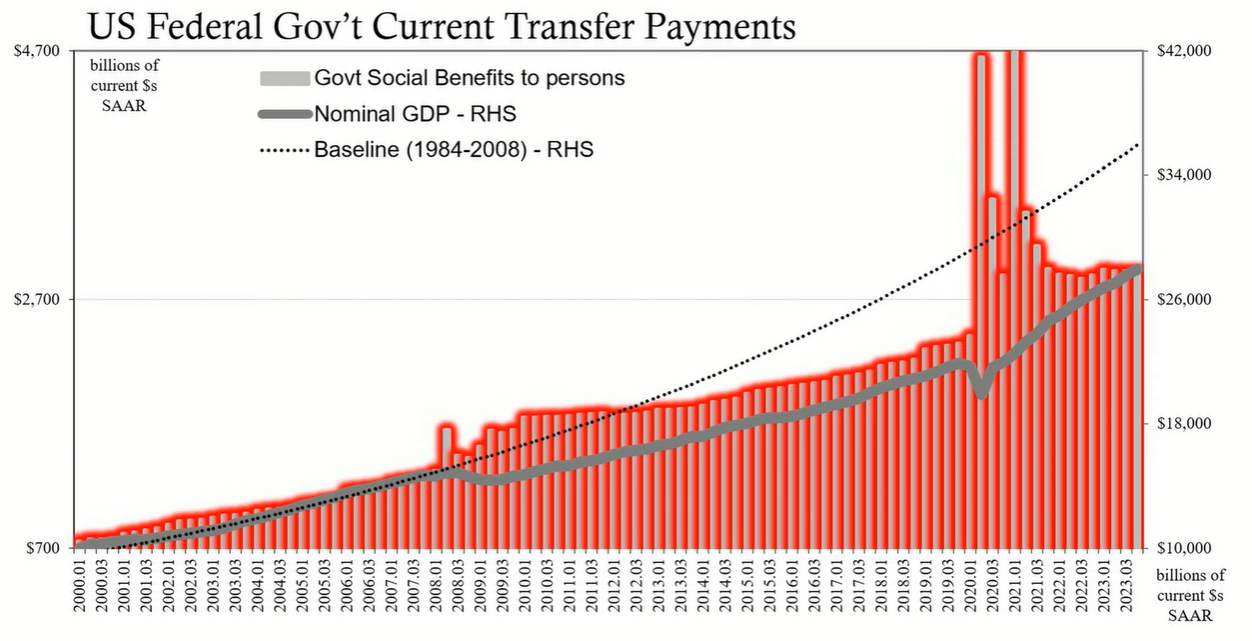

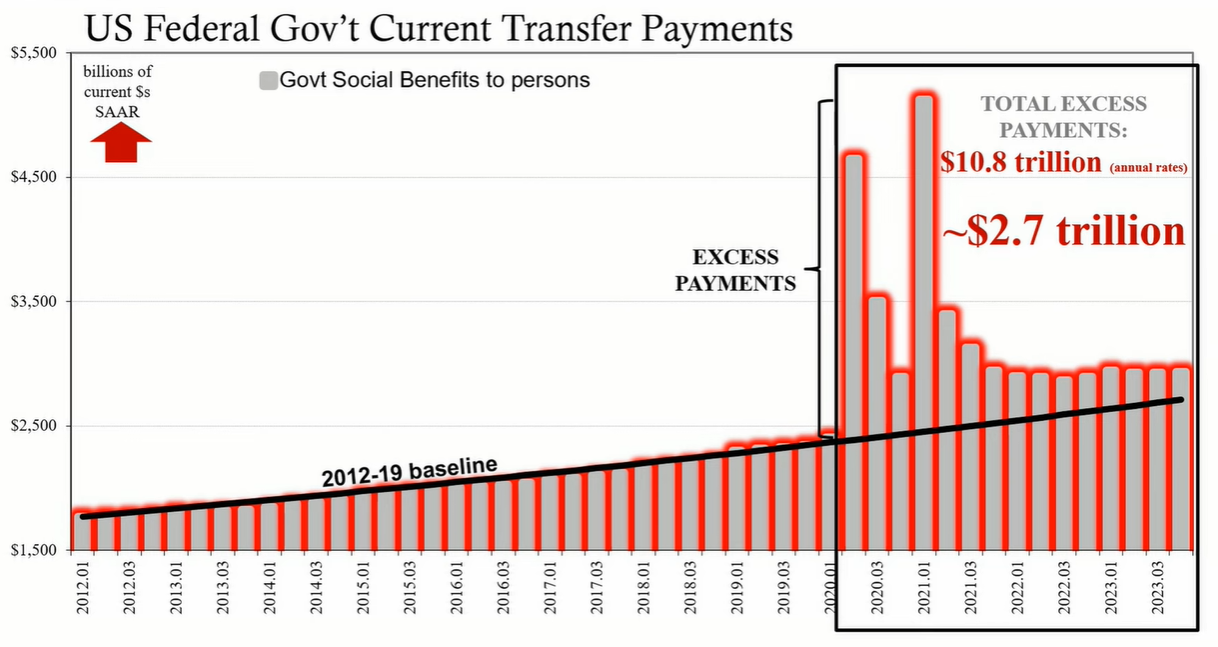

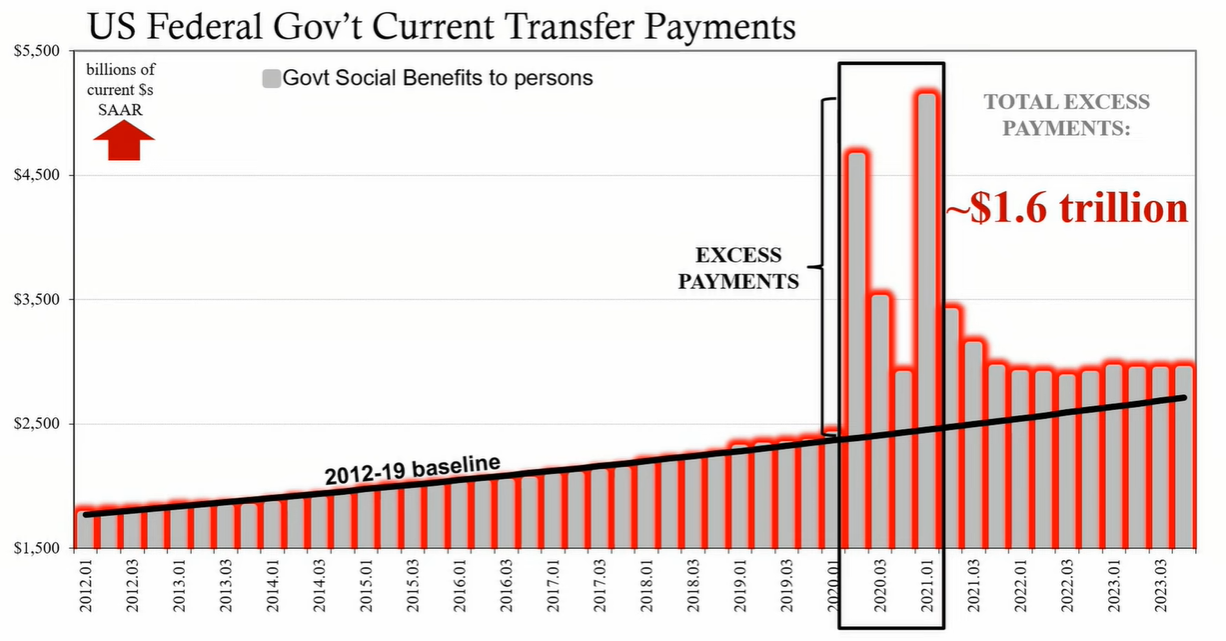

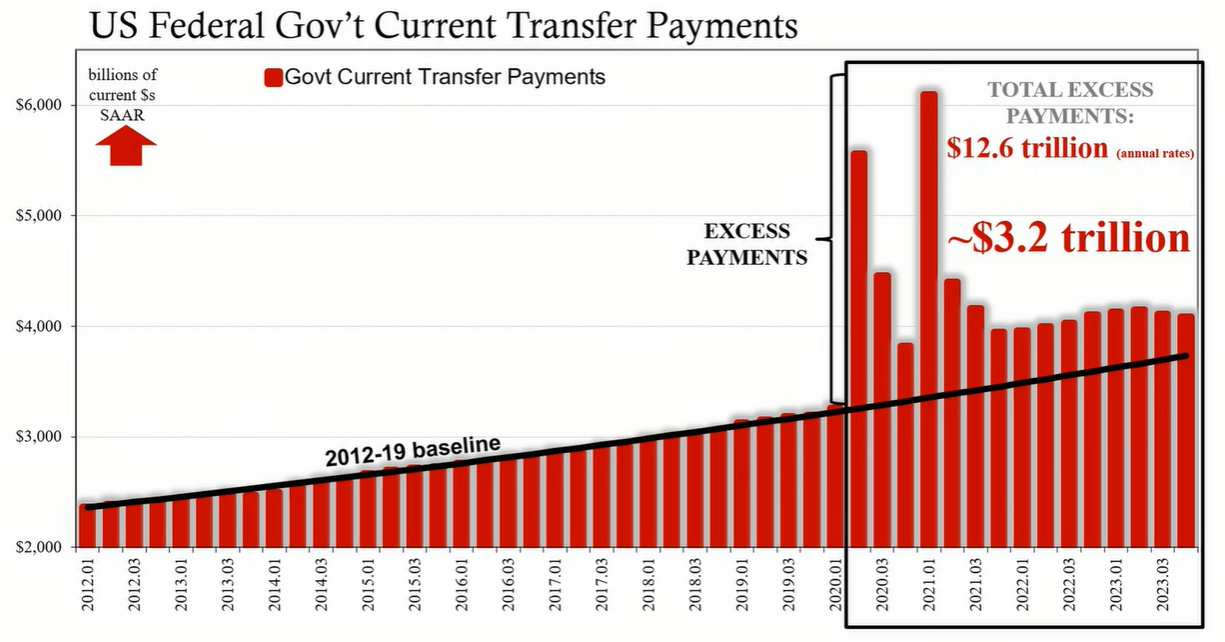

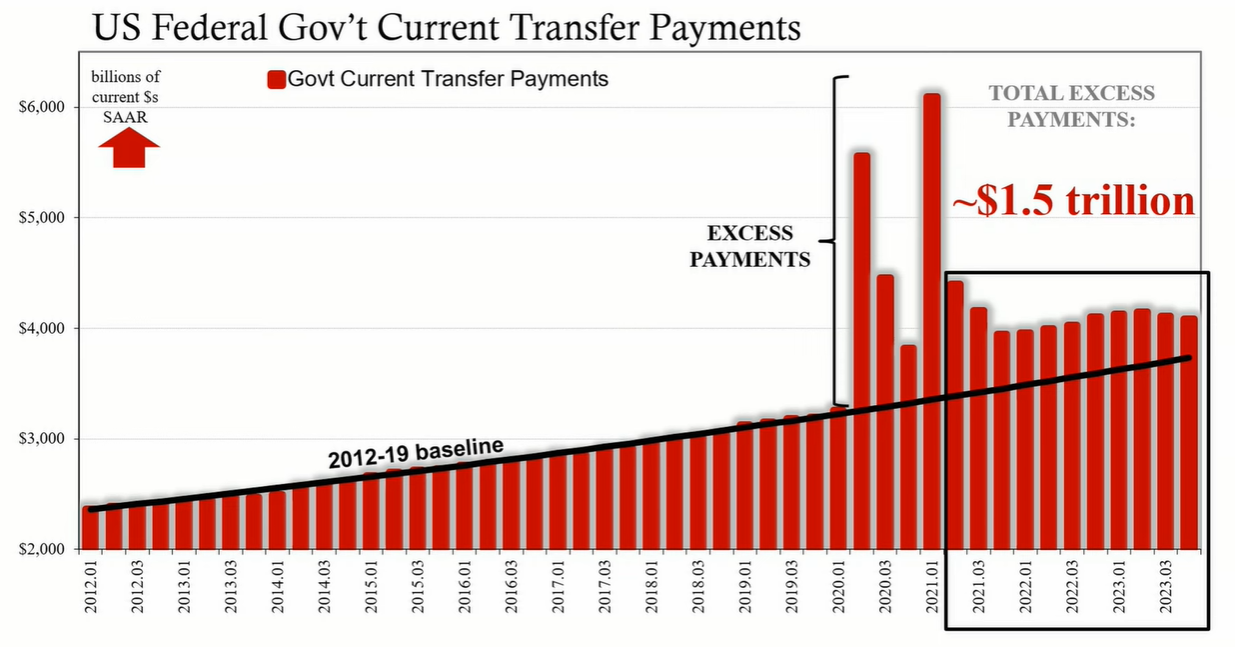

To understand the scale of government transfers, we can compare the period of 2012 to 2019 with the subsequent years. The excess in government social benefits to persons beyond the pre-pandemic baseline calculates to roughly $2.7 trillion. Notably, $1.6 trillion of this was during the initial phase of the pandemic. The excess continued post-2021, with a notable $259 billion in the last year.

When considering total current transfer payments, this figure reaches approximately $12.6 trillion over the last four years. This suggests an estimated $3.2 trillion in real money excess payments, with $1.5 trillion in additional transfers occurring after the first pandemic period.

The massive government transfers have been financed by borrowing from hedge funds and other private savings, funneling money into the real economy for non-economic reasons. As these excess payments begin to dissipate, the question arises about the economy's trajectory without this governmental support.

Keynesian economists believe in the concept of "automatic stabilizers," which are supposed to kick in during economic downturns and lead to recovery. However, the effectiveness of these stabilizers is disputed, as they may also hinder recovery by introducing non-economic factors that delay necessary economic adjustments.

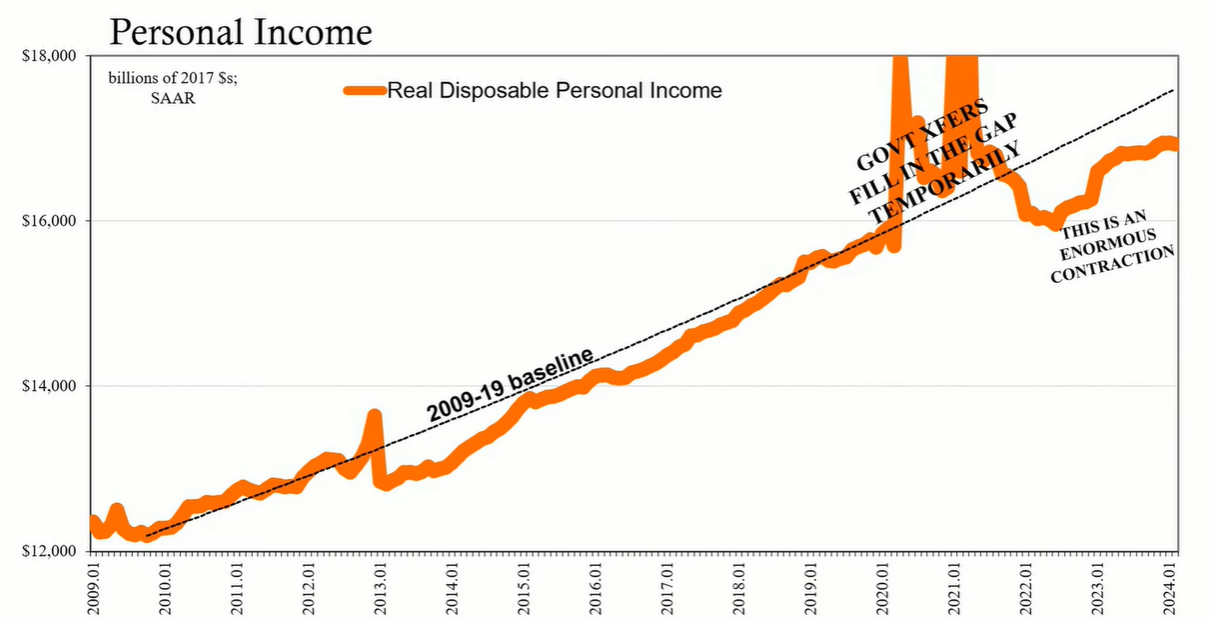

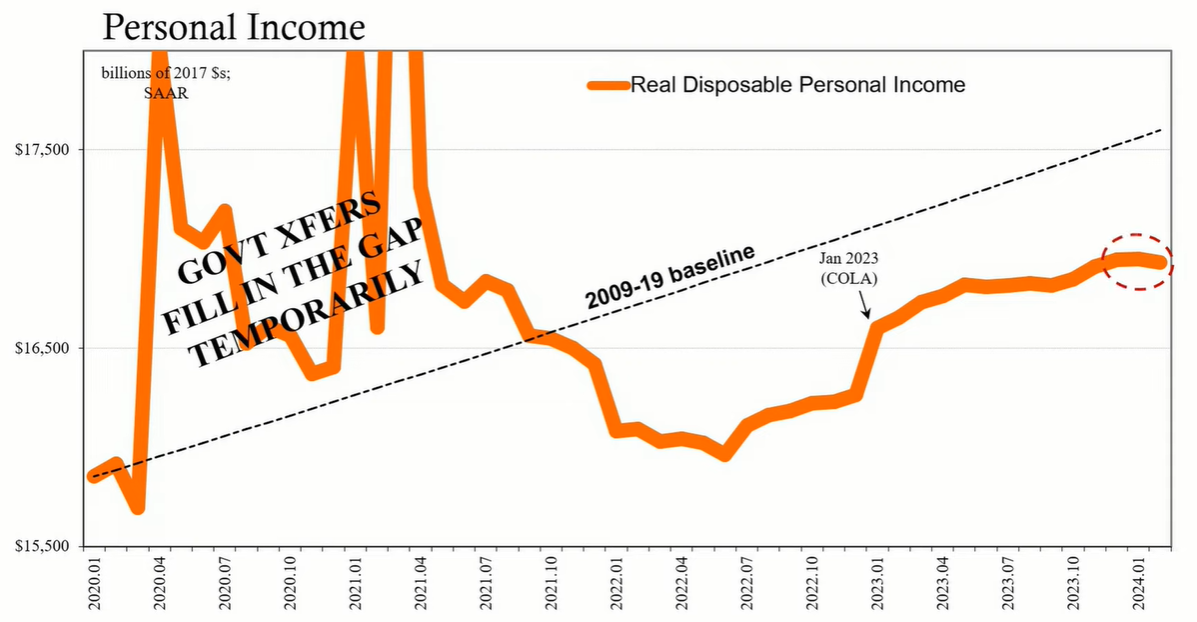

Despite the large-scale transfers, disposable personal income has not kept pace with inflation, indicating that these efforts have not bought a recovery. The economy remains unstable and is still seeking a new equilibrium after years of distortions.

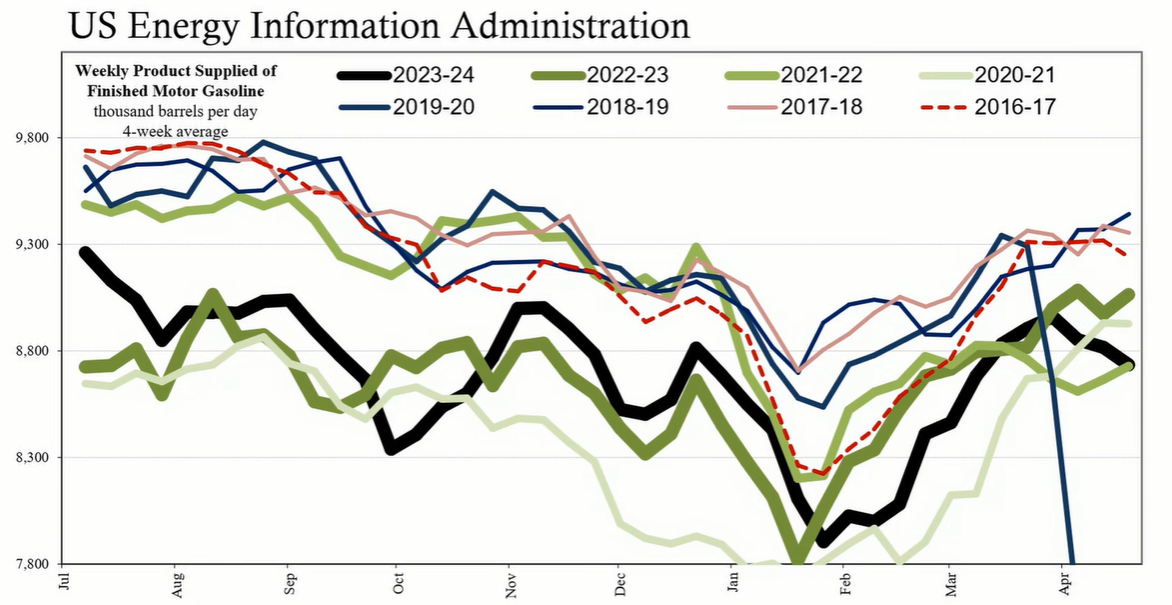

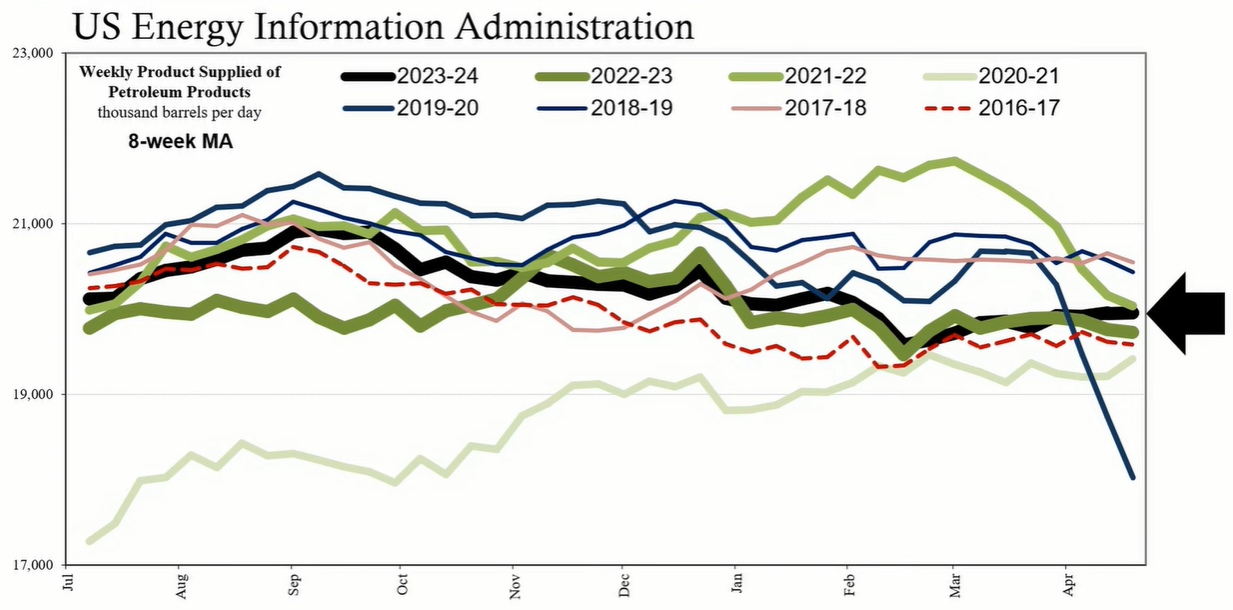

Recent data shows a sharp drop-off in gasoline demand, signaling ongoing demand destruction. Energy Information Administration figures reflect a significant decrease in gasoline use, suggesting economic weakness. Petroleum supply also indicates a similar trend, reinforcing the notion of an economy that is not as robust as the transfers might suggest.

Europe has experienced the downside of the supply shock more visibly, with a recession evident in its recent GDP figures. The US, bolstered by excess transfers, has avoided a similar fate, but this may not be a sustainable or desirable outcome.

The US economy is facing challenges that transfers alone cannot resolve. As demand destruction manifests and excess payments subside, the reality of the economic situation becomes clearer. The economy must find a stable equilibrium, and the prolonged distortions may ultimately require a more painful but necessary adjustment.