It was simply ledger entries on internal books at the reserve bank- it didn’t exist anywhere else.

The Genesis of the Eurodollar is shrouded in mystery. But it would eventually grow to be more powerful than anyone could have imagined.

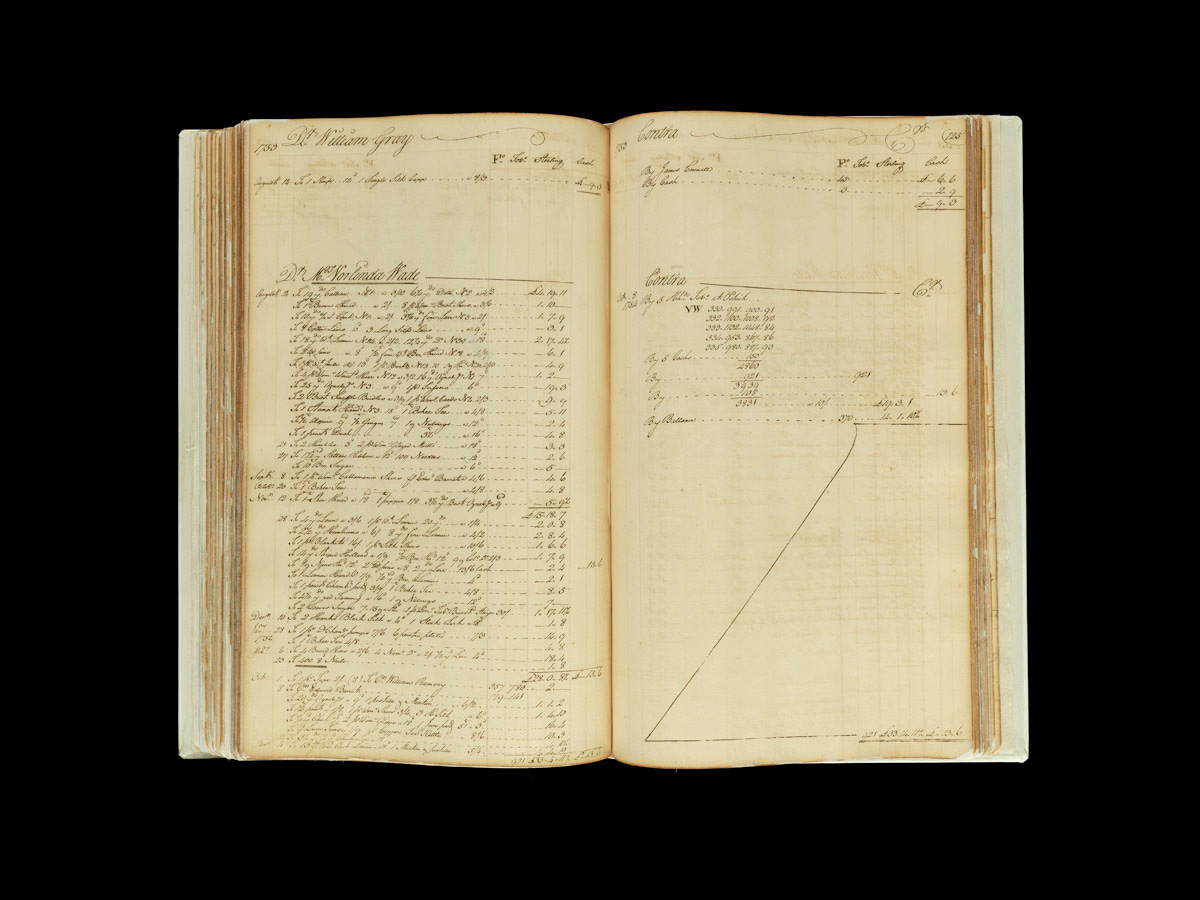

To fully understand the structure and history of the Eurodollar system, we first need to understand ledger money. Ghost money has existed for hundreds of years. Jeff Snider points out in Eurodollar University, that despite what many people think, the transition away from a true gold standard happened long ago, and the system that the United States and other industrialized capitalist economies worked with since the 1600s was not a true “gold” based standard, but rather a gold reserve standard. Banks would accept gold and silver in specie and write banknotes, which were originally gold warehouse certificates, to prove ownership of the gold in the account. These notes could then be traded freely with each other, but no standard denomination or issuer was originally present.

As banks evolved in the late 1700s and early 1800s, it became clear that the gold reserve standard, which remedied the flaws of a gold standard (think of carrying around coin purses filled with gold and silver, and having to make and ask for exact change everywhere) was also flawed. Banks still had to hold gold reserves physically at branch locations, and as economic growth stimulated trade and commerce, this meant that more and more trade occurred and the notes they issued were circulated more widely. Problems began to arise when travelers, going from one town to another, would bring banknotes from their town into the new one. For example, if a merchant was living in Brunswick, NJ and went into Boston, they would attempt to use their Brunswick banknotes in trade or financing for a voyage. Most Boston shops would not accept these notes, as they were unaware of the creditworthiness, so the merchant would have to go to a local bank or money market, where money traders would evaluate the value of the note and trade it for a local note, usually below par. (I.E., they would buy your Brunswick notes for 90c on the dollar for a local note).

Thus, Brunswick banknotes could build up in a Boston bank, and without a correspondent reserve system, there was no way for the Brunswick bank to settle these credits except by receiving the banknotes physically and redeeming them for gold or silver.

The issue is, knowing that many of its notes would be taken far away and likely not be redeemed for gold, many rural banks had an incentive to issue excessive amounts of banknotes in hopes that they would circulate in far-flung locales and never be brought back for specie (payment in physical gold/silver).

In spite of its imperfections and challenges, the decentralized structure of the pre-Civil War banking system afforded banks the freedom to independently explore ways to enhance the system. It is not well known that one of these innovations was a private American bank that brought organization and convenience to numerous privately issued bank notes.

Boston, as the region's primary financial center, experienced a proliferation of circulating bank notes. Some notes originated from Boston banks, widely recognized as solvent by the local community. However, others were issued by state-chartered banks, often situated at a considerable distance. In those times, the distance posed obstacles to both obtaining comprehensive information about the solvency of these banks and easily redeeming their notes into gold or silver. Initially accepted at face value in Boston, the notes from distant banks led some of them to issue more notes than they could back with gold. Consequently, these country bank notes began to be traded at discounts to their face value, ranging from 1 percent to 5 percent.

Money brokers soon arose, traders who would buy rural banknotes at discount and then literally transport the notes to the banks deep in the state’s interior for redemption in specie (physical gold or silver). These brokers were hated by the bankers, but served an essential role as they helped to limit the money supply growth of these distant financial institutions. In 1814, the New England Bank of Boston declared its entry into the money broker business. It started accepting country notes from holders and facilitating their redemption by forwarding them to the respective issuing banks. Over the following years, notes from city banks became a diminishing fraction of the overall money supply in New England, as country banks were issuing a significantly larger volume of notes relative to their capital (i.e., gold and silver) compared to the Boston banks.

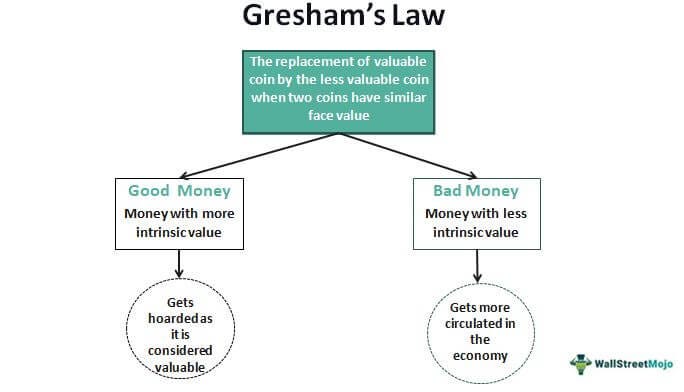

Worried about the increasing presence of lower-value paper currency, both the Suffolk Bank and the New England Bank resumed the practice of buying country notes in 1824. However, their objective this time was not to profit from redemption but rather to decrease the quantity of country notes circulating in Boston. They held the deluded belief that by doing so, there would be a rise in the usage of their superior notes, ultimately leading to increased loans and profits for their banks. However, the more they acquired country notes, the more notes of even lower quality, particularly from distant Maine banks, would take their place.

(See Gresham’s Law)

Given the increased risk associated with these notes, the Suffolk Bank proposed to six other city banks the establishment of a joint fund to purchase and return these notes to the issuing banks for redemption. This coalition of seven banks, referred to as the Associated Banks, successfully raised $300,000 for this purpose. Acting as the agent and purchasing country notes from the other six banks, the Suffolk Bank initiated operations on March 24, 1824. The volume of country notes procured through this mechanism significantly expanded, reaching $2 million per month by the end of 1825.

By that point, the Suffolk Bank had gained sufficient strength to operate independently. Additionally, it had the influence to compel country banks to deposit gold and silver with the Suffolk Bank, thereby facilitating easier note redemption. By 1838, nearly all banks in New England had complied with this arrangement, redeeming their notes through the Suffolk Bank.

The operating principles of the Suffolk system were: Each country bank was mandated to uphold a permanent specie deposit of at least $2,000, with larger requirements for larger banks, covering the potential redemption of all notes received by the Suffolk Bank. These gold and silver deposits were not necessarily required to be held at Suffolk but had to be located conveniently to ensure notes could be redeemed without being sent back to the issuing bank. However, in practice, the majority of reserves were held at Suffolk. City banks had a fixed deposit requirement, which decreased to $5,000 by 1835. Although no interest was paid on these deposits, the Suffolk Bank provided a crucial service in return: it committed to accepting, at par, all the notes deposited by other New England banks in the system, crediting the depositor banks' accounts on the subsequent day.

By serving as a "clearing bank" that accepted, sorted, and credited bank notes, the Suffolk Bank facilitated a system where any New England bank could now accept the notes of any other bank, regardless of geographical distance, at their face value. This significantly reduced the time and inconvenience associated with seeking specie redemption from each bank individually. Furthermore, a sense of certainty developed that the notes of member banks associated with the Suffolk system would be honored at par. This assurance initially gained traction among fellow bankers and eventually permeated the general public. Trust is a banks’ most powerful asset- and greatest liability if it is lost.

Suffolk's most potent tool for maintaining stability was its authority to confer membership into the system. It exclusively admitted banks whose notes demonstrated sound financial health. While Suffolk couldn't prevent a poorly managed bank from issuing excessive notes, refusing membership ensured that those notes wouldn't gain broad circulation. Furthermore, member banks facing mismanagement could be removed from the roster of Suffolk-approved New England banks in good standing. This swift action led to an immediate discounting of the offending bank's notes, even if the bank continued to redeem its notes in specie.

The Suffolk Bank played a crucial role in preventing excessive issuance of these notes. Essentially, it functioned as a private central bank that ensured the integrity of other banks. In doing so, it transformed New England into a bastion of monetary stability at a time when the rest of America grappled with currency turmoil.

Although the bank eventually failed and was wound down, the Suffolk served as an prototype of a reserve bank.

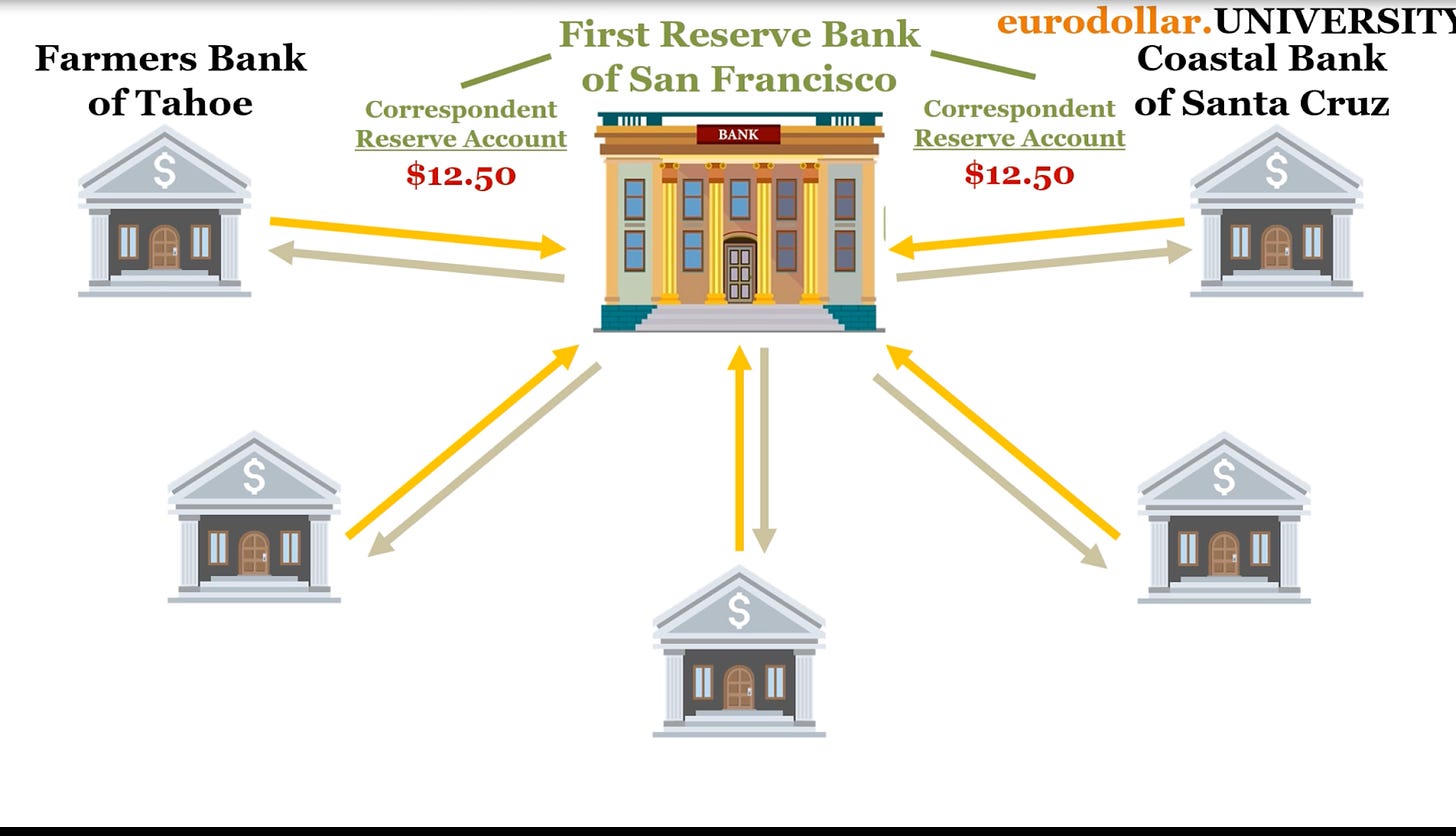

Reserve banks existed in major cities, and would facilitate trading of bank reserves (genius, I know). The bank system thus became a pyramidical structure, where the largest reserve banks were custodians of bank money for hundreds of city banks, which were custodians for thousands of rural banks. Again, stealing a graphic from Eurodollar University here-

Thus, when the Federal Reserve was created- it wasn’t some newfangled and innovative idea. It was simply an adaptation of the system that had existed before. The new contraption added to the Fed was the creation of the money printer- the ability of a central bank to loan unlimited amounts of bank reserves to correspondent banks in crisis to fulfill their capital management needs.

Prior to the creation of the Fed, reserve banks existed but were limited in the amount of loans they could create without risking insolvency.

Thus, this system, which was still ostensibly on a “Gold Standard”, now obviated the need for physical gold, indeed even dollars (for banks)- because this new creation, bank reserves, could be traded in between institutions looking to maintain solvency. The reserves represented a claim on physical gold or cash, but rarely were ever called. Thus credit creation could be expanded more than ever before.

Most money in this sense was now “ghost money”, a term Snider uses to explain this third-order derivative of the base money, gold. It was simply ledger entries on internal books at the reserve bank- it didn’t exist anywhere else.

Originally written on Dollar End Game